Rhode Island Freemasonry during the American Civil War

In Kennedy Plaza is the Soldiers & Sailors Monument, and on its tablets are etched the 1,727 names of Rhode Islanders who made the ultimate sacrifice to preserve the Union and free men and women from the bonds of servitude

Introduction

One of the amazing aspects about our little state is its history not only about our nation, but our Masonic past. With everything going on today in our crazy world, its sometimes difficult to compare our own hardships with those of our ancestors and past brothers. In Kennedy Plaza stands a 40-foot-tall granite monument adorned with dark bronze oxidized tablets and statues of soldiers, sailors and old Columbia.

This is the Soldiers & Sailors Monument and on its tablets are etched the 1,727 names of Rhode Islanders who made the ultimate sacrifice to preserve the Union and free men and women from the bonds of servitude during the American Civil War. Among these names are brothers of the Craft who firmly believe these tenents of Union and freedom and paid for these convictions with the ultimate price they could give.

Freemasonry of the 19th Century

In the years prior to the war, Freemasonry in Rhode Island had experienced its own period of trials and tribulations during the anti-Masonic period of the 1820s and 1830s and the Dorr Rebellion of the 1840s. During this time of political and social unrest, many lodges surrendered their civil charters to the Grand Lodge and went underground for a time. By the late 1840s into the 1850s, membership began to increase and saw major growth by the late 1850s. Throughout the war, Rhode Island Masonry would be led by M∴W∴Ariel Ballou Grand Master from Morning Star Lodge No. 13 of Woonsocket. Around the country, there were an estimated 500,000 Masons. Many would enlist to fight for either the North or South in the upcoming conflict.

Rhode Island the First to Answer

On the morning of April 12, 1861, the peaceful skies around Charleston harbor, South Carolina were forever shattered as merciless Confederate artillery assailed the Union held Fort Sumter. While the southern states began to prepare for war with the federal government in Washington, DC, Rhode Island politicians, citizens, and Masons heard the news. Since the Revolution, Rhode Island had transformed from a rural and maritime trading center to one of New England's primary textile and tool manufacturing producers, in cities such as Providence, Woonsocket, and Pawtucket.

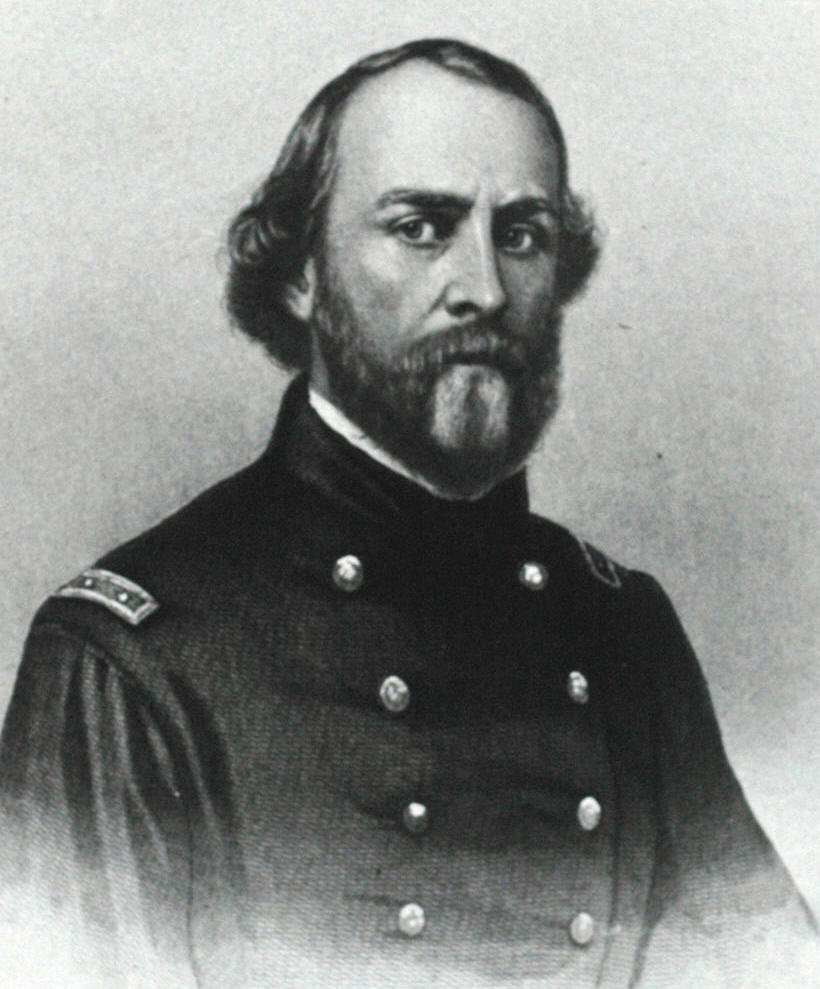

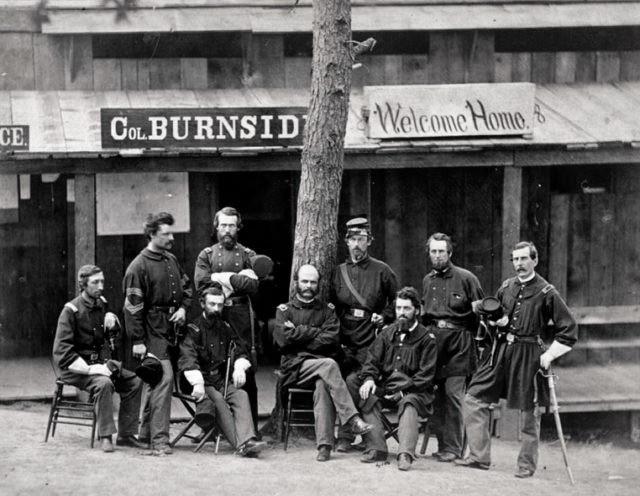

President Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteers to end the rebellion was answered post haste by Rhode Island. Governor William Sprague IV along with other influential Rhode Islanders began the process of raising troops. He telegraphed a West Point graduate and former army officer about taking command of the Rhode Island troops. This former officer had been stationed at Fort Adams in Newport and was now employed by the Illinois Central Railroad. This man was Ambrose Burnside, and he immediately accepted Governor Sprague’s offer.

|

Regiments such as the 1st Rhode Island Detached Militia Infantry and the 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery, Company A were composed of men from various town militia units such as the Kentish Guard and the Providence Marine Corps of Artillery that served as the foundation of military order and discipline for future infantry and artillery regiments.

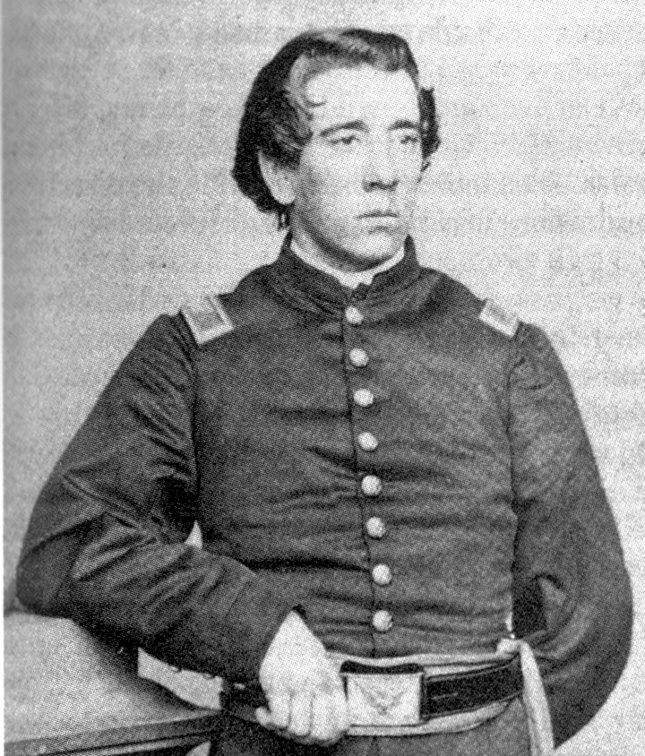

Masonic brothers from around the state enlisted in order to preserve the Union. As Brother Sullivan Ballou of Morning Star Lodge No. 13 of Woonsocket explains in a letter to his wife, Sarah, before leaving Providence for Washington, "our movement may be one of a few days duration and full of pleasure and it may be one of severe conflict and death to me. Not my will, but thine O’ God, be done. If it is necessary that I should fall on the battlefield for my country, I am ready. I have no misgivings about, or lack of confidence in the cause in which I am engaged, and my courage does not halt or falter. I know how strongly American civilization now leans upon the triumph of the government, and how great a debt we owe to those who went before us through the blood and suffering of the Revolution. And I am willing, perfectly willing to lay down all my joys in this life to help maintain this government and to pay that debt."

|

Many lodges around the state expedited degrees upon candidates and had annual dues paid for those enlisting. As the case with Brother John H. Sweet of Mount Vernon No. 4 who at the outbreak of war served as Senior Deacon. With brothers flocking to fill the ranks of the Union Army, the Grand Lodge of Rhode Island saw fit to establish a traveling military lodge for brothers to continue to practice the Craft while serving. American Union Lodge was granted a dispensation and charter with brothers from the 1st Rhode Island Infantry Volunteers forming the membership. On April 18, 1861, soldiers and cannons from Battery A arrived in Washington establishing Camp Sprague, followed by the 1st RI Infantry on April 20, 1861, and the 2nd RI Infantry and another artillery battery in May at the mustering point.

|

The Battle of Bull Run, Virginia

On July 21, 1861, the Union Army departed its encampment outside of Washington to confront the Confederate forces converging at Manassas junction near Bull Run Creek. That morning the Rhode Island brigade under Brigadier General Ambrose Burnside formed the vanguard of the Union attack at Matthew’s Hill, firing some of the first volleys of the war.

|

At that instance, Brother Slocum fell mortally wounded from an enemy bullet that struck his head. Brother Slocum, who was one of the few men with military experience prior to the Civil War, his death shocked his men who continued to fight until ammunition became scarce. With reinforcements lead by General Thomas 'Stonewall' Jackson, the Confederates were able to turn defeat into victory and rout the Union Army.

When news of the defeat reached home, Masonic bodies and citizens alike mourned the losses at Bull Run. At Mt. Vernon Lodge No. 4, the secretary’s minutes read during the August 15 meeting, "our brother, John S. Slocum, was slain at the Battle of Bull Run, in Virginia, while leading the 2nd Regiment of Rhode Island Volunteers in the defense of his country…He has fallen in the noble effort to prevent the destruction of our glorious Union of States. In a token of our respect for his memory, our altar will be draped in mourning for the space of thirty days."

|

This was not the only action by Masons to honor the memory of their deceased brothers. A Masonic committee was established and with the support of Governor Sprague, citizens returned to the battlefield to reclaim the bodies of the state’s fallen soldiers and return them home.

In March of 1862, the party lead by Governor Sprague traveled to Virginia and exhumed the remains of Brother Slocum and others from their shallow graves at Bull Run. Brother Ballou’s remains could not be found. Locals informed the Rhode Islanders that in the aftermath of the battle, a group of Confederate soldiers wishing to desecrate the remains of Colonel Slocum in retribution for the regiment’s gallant performance during the battle, mistook Brother Ballou’s body for Slocum. All that was retrieved of Brother Ballou was some scraps of uniform, charred bones, and ash.

When the party returned to Rhode Island, the remains of Brother Slocum and Ballou were interred at Swan Point Cemetery in Providence on June 22,1862. The Masonic funeral procession was composed of brothers and officers of Mt. Vernon Lodge, Morning Star Lodge, Cavalry Commandery, and the Grand Lodge of Rhode Island, under the direction of M∴W∴Ariel Ballou Grand Master.

|

The first major engagement would have lasting impacts upon the public’s conscience for the rest of the war. Soon those brothers on the home front would be tested, not by bullets and the fatigue of battle, but care for the wounded and financial aid to the widows and families of deceased brothers.

The Bloodiest Day for Rhode Island

The reminder of 1861 to 1862 saw our brothers in the service fighting multiple military campaigns from the east to west. Rhode Island units contributed to Union successes at Shiloh, General Burnside’s coastal campaign in North Carolina, and Antietam. Thus, halting the Confederate advance into Union territory and giving President Lincoln victory he needed to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. This political executive order changed the reason of fighting the war, to not only preserve the Union, but to destroy the institution of slavery in the southern states and freeing African Americans from its yoke.

In December of 1862, under pressure from the War Department and President Lincoln, General Burnside who had reluctantly taken overall command of the Union’s Army of the Potomac in its Eastern theatre ordered the army to attack the Confederate army under General Robert E. Lee at Fredericksburg, Virginia in hopes to end the war. December 13, 1862 would be the single bloodiest day for Rhode Island.

Wave after wave of blue coated soldiers were sent to storm the heavily fortified Confederate positions on Marye’s Heights but were repulsed by brutal unrelenting canister fire and Minié balls. The 12th RI Infantry disintegrated under fire leaving the 7th RI Infantry to advance alone losing a man every yard. As one Union soldier stated observing the carnage, "Barrels of blood had been poured on the ground."

At dusk of that December day, seventy-five Rhode Islanders were dead and another three hundred more wounded. Brother George Bucklin, a member of Mount Vernon Lodge, Company K, 12th R.I. Infantry was one of the wounded; succumbing to his injuries on January 9, 1863. He was twenty-four years old at the time of his death. The aftermath of the disastrous defeat saw General Burnside step down as commander of the Army of the Potomac and take a command in the Western Theatre of the war.

Friend to Friend

Although the growing casualties greatly hampered military moral and public opinion of the war, acts of generosity and kindness were demonstrated by both sides during the conflict.

This kindness and care for the wellness of brother Masons took shape in many forms and actions over the course of the war. Particularly on the battlefield when caring for the dying and interment of remains of brothers regardless of which flag they followed. Masons who found themselves captured in battle who identified themselves as brothers in the Craft, received medical care and letters sent home by brother Masons such as the infamous Andersonville Prison in Georgia.

One instance relates to future president and Mason, William McKinley who described an event in his diary while accompanying a Union surgeon to care for wounded rebel prisoners of war. As they walked, he noticed the doctor shaking hands and distributing a roll of bills to some prisoners. Astonished at these actions, McKinley asked the man if he had known those men. The surgeon replied, "No, but they identified themselves as my brothers." When McKinley questioned if he would receive the money back. The surgeon stated, "If they are able to return the money they will, but it makes no difference to me; they were Masons in trouble, and I am only doing my duty as a Mason." Reflecting on this, McKinley wrote in his diary, "If that is what Masonry is, I want some for myself".

The climax of fighting during the war happened in July 1863 at a small crossroads town in Pennsylvania. It was here the Confederate army of General Lee fresh off a string of victories and the Army of the Potomac battered and bloodied under General Gordon Meade converged at Gettysburg. It was here that over 180,000 soldiers, 18,000 being Masons, engaged in some of the bloodiest fighting of the war; of this number over 50,000 would be casualties by July 3, 1863.

Future brother of Harmony Lodge and Grand Master of Rhode Island, Elisha Hunt Rhodes, a former corporal now captain in the 2nd RI Infantry kept a diary of his experience during the war, discussed a Masonic burial while fighting continued at Gettysburg. A fellow captain in the regiment had told him of a dead Georgia colonel who had been identified as a Mason, and with the assistance of other Masons in the Union ranks had buried their fallen brother. Captain Rhodes was rather confused by the ordeal admitting in his writings that he was not a Mason and did not understand this treatment for the enemy dead. Captain Rhodes would eventually receive a furlough and return to Rhode Island and join the Craft in 1864.

|

Probably the most famous act by Masons during the war was between Brigadier General Lewis Armistead and Captain Henry Bingham. On July 3, General Amistead heroically led the Confederates that pierced the Union line during Pickett's Charge. Fierce fighting ensued and Amistead was wounded. From accounts, Brother Amistead gave the sign of distress, "as the son of a widow."

Just prior to this, General Winfield Hancock, a Pennsylvanian Mason and good friend of Brother Amistead prior to the war, was also wounded. Captain Henry Bingham, aid-de-camp to General Hancock and a Philadelphia Mason, with other brothers came to the aid of Brother Amistead. Amistead identified himself and entrusted Brother Bingham with his personal belongings including his Masonic watch to give to his friend, Brother Hancock. Brother Amistead was moved for treatment to a Union field hospital where he died days later from his wounds.

|

Gallantry on the Fields of Battle

The victory at Gettysburg had invigorated the Union. President Lincoln now sought a commander who could finally entrap Lee's army and crush the rebellion. General Ulysses S. Grant, fresh from success at Vicksburg, Mississippi, was selected for the task. From 1863 to 1864, Grant pursued Lee in a succession of swift decisive battles during the Overland Campaign.1863 to 1864, Grant pursued Lee in a succession of swift decisive battles during the Overland Campaign.

Many Rhode Island Masons distinguished themselves in battle during this time. Brother Horatio Roger, Jr. and Nelson Viall of Saint John's No. 1 Providence were promoted for gallantry in combat, both would eventually receive a brevet promotion to Brigadier General.

Brother Viall would take command of the Rhode Island 14th Colored Heavy Artillery Regiment, composed of freed African Americans and officers selected with battlefield experience. The regiment was assigned to New Orleans, Louisiana where it conducted engineering and fortification maintenance. Brother Viall along with other regimental officers established a school for its enlisted soldiers, many who were illiterate and could not write.

|

The Horrid Pit, Petersburg Siege 1864

In the East, Grant forced Lee to fortify the city of Petersburg, Virginia in a prolonged siege. General Burnside returned to the Eastern Theatre and recommended an audacious plan to break the siege.

In the early morning of July 30, 1864, Union sappers detonated a mine under Confederate trenches, creating 35 feet deep, 170 feet across, and 120 ft wide crater. Over 8,000 of Union soldiers including many from Rhode Island stormed the breach only to be trapped once the Confederate defenders regrouped.

The Battle of the Crater resulted in almost 4,000 Union casualties. The 4th RI Infantry lost over half its strength at the end of the fighting reduced to less than two hundred men.

Masonry and the Home Front

On the home front, there was not one Mason who did not have a relative, friend, or Masonic brother in uniform. Degree and regular work continued, and large classes of Masons were raised. Annuals often became public displays of patriotism and support towards the armed forces and President Lincoln.

On February 23, 1865, the Providence Press published an article detailing the annual public banquet of Mount Vernon Lodge. Over two hundred Masons, ladies, and guests were in attendance. Toasts were offered to President Lincoln, the Union, and even General Burnside sent a personal letter to the lodge offering his thanks to the lodge brethren for their invitation and gratitude at being asked to be the keynote speaker for the evening and offered a toast to overall victory. Not knowing the war would be over in a month's time.

Honor Answers Honor, Appomattox

On April 2, 1865, Brother Rhodes now Colonel of the 2nd RI Infantry, led his men and stormed the trenches of Petersburg. One week later, General Lee formally surrendered to General Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia on April 9, 1865. Brother Rhodes and his regiment who had opened the war four years prior at Bull Run were witnesses to the end of the conflict.

After General Lee's surrender, a column of Confederate soldiers under General Gordon, a Georgian Mason, surrendered their arms and colors to General Joshua Chamberlain, a Mason of Maine, and his brigade. Upon viewing the Confederates, General Chamberlain ordered his men to present arms in salute of their defeated adversary. General Gordon, seeing this, returned the salute to this Union officer and Masonic brother. The War between the states was over.

|

The End of the War

With the end of the war and events of President Lincoln's assassination, the men of the Union armies were mustered out of service. Back home, veterans returned to a heroes' welcome. Many formed chapters of the Grand Army of the Republic, G.A.R. fraternity to remember their fallen comrades, tend grave sites, and decorate graves every May on Decoration Day now Memorial Day. Brothers Slocum and Ballou's graves received new tombstones donated by funds from members of the state's chapters. Rhode Island was one of the first states to recognize Decoration Day and formerly adopted it in 1872.

During the years after the war known as the Reconstruction Era, many Masonic lodges received requests for financial aid to assist their brothers in the war-ravaged South.

|

These actions display the humanity of man during this horrific fighting. Brothers contributed to the humanitarian treatment of their fellow Masons regardless of side and the proper respect to those who died. Masons displayed the utmost loyalty and duty to one another that truly transcended political or personal ideologies and set the example for future brothers of the Craft.

Recorded in the July 26, 1866 secretary's minutes, show that a Masonic committee from Columbia, South Carolina had sent a request to Mount Vernon Lodge for financial assistance to rebuild their Masonic temple and replace their jewels and working tools that had been destroyed during the war.

Upon receiving letters of financial aid for the children of deceased and indigent Masons from the Grand Secretary and Richland Lodge No. 214, Mount Vernon contributed $25.00 per child in Thomasville, North Carolina. Brother Dennis Terrill received a Master Mason's silk apron found in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, by a returning soldier and hoped to return it to its proper owner.

Many brothers and veterans who had returned to the Ocean State, would find success in their civilian careers. Although disasters plagued his military career during the war, General Burnside remained a popular leader among his troops and the general-public especially in Rhode Island where he served as governor and senator after the war. Governor Sprague would continue to support the Union cause during the war as a senator and eventually retired to Paris, France. Brother Horatio Rogers, Jr. became Attorney General for Rhode Island. Brother Viall was appointed the first police chief of Providence and warden of the state prison in Cranston. Brother Rhodes returned to Rhode Island and became a successful businessman and served the Craft as Grand Master of Rhode Island in 1893.

The Soldiers and Sailors Monument

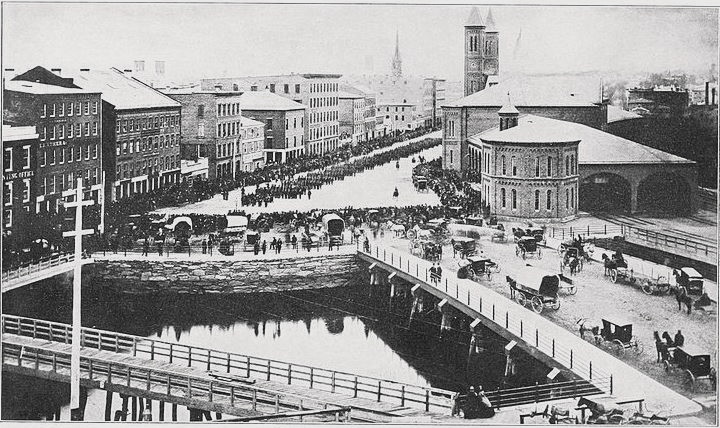

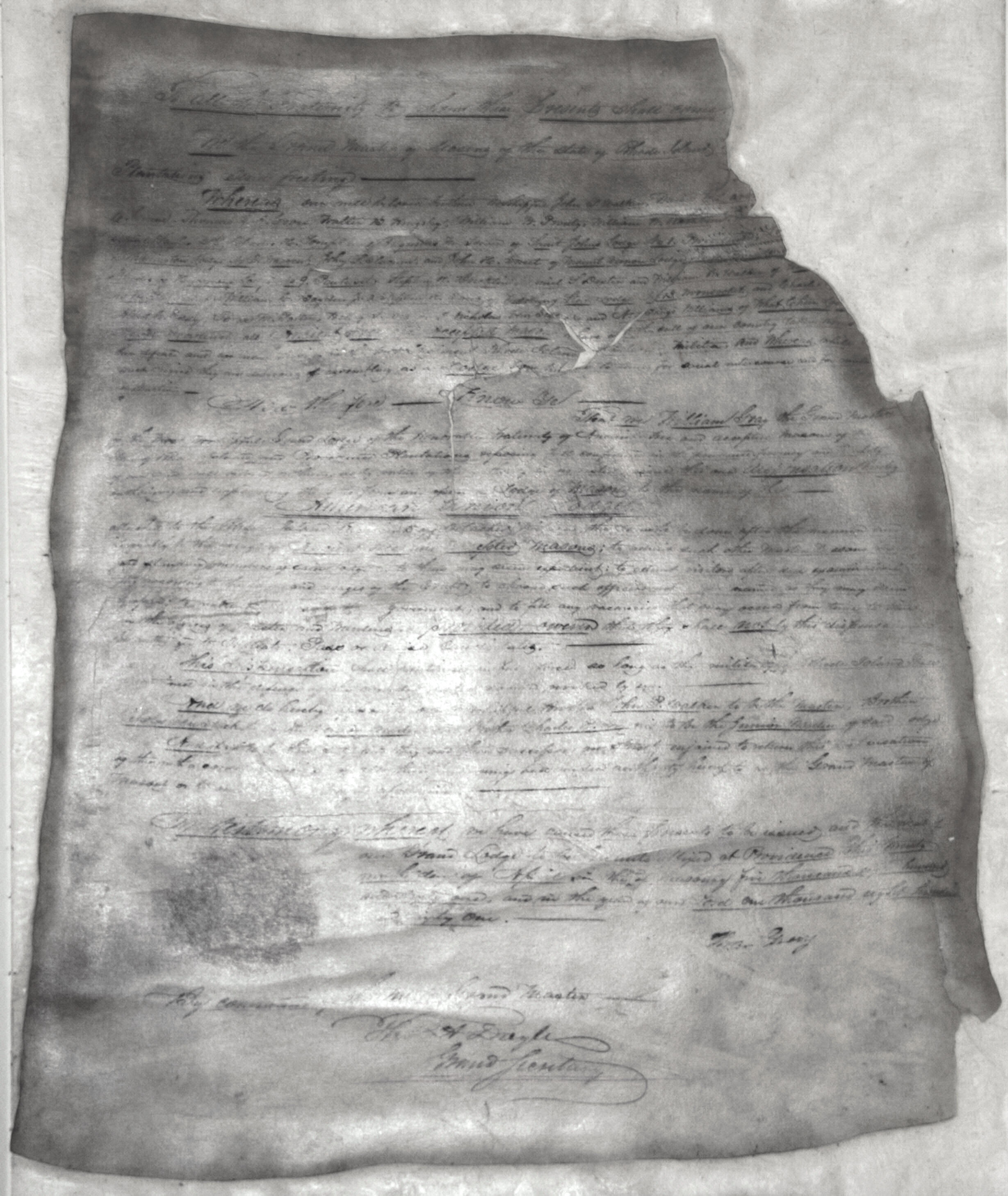

Since the end of the war in 1865, the granite quarries in Westerly produced the stones that would be used in the erection of countless memorials and statues dedicated to the memory and heroism of Rhode Island's fighting men in the crusade to free the slaves and preserve the Union. Citizens of Providence and veterans of the G.A.R. saw fit to dedicate a memorial at the west end of Exchange Place in Providence to reflect the honor and memory of all those Rhode Islanders who made the ultimate sacrifice. At the request of the Rhode Island General Assembly, the Grand Lodge was asked to lay the cornerstone for the monument.

|

On June 24, 1870, thousands of spectators, state, and federal officials, widows & children, veterans, and others from across the country came to view the dedication of the Soldiers and Sailors Monument. Twenty-two lodges and two Royal Arch Chapters were in attendance alongside six Commanderies and the detached mounted Sir Knights of Cavalry Commandery No. 13. M∴W∴Thomas A. Doyle of St. Johns Lodge No. 1 Providence presided over the ceremony.

A Brotherhood Undivided

The end of the war brought the nation to a new chapter of its history. The trials of the war had reformed the nation but would take many years and even decades to heal, even to some extent, into today.

The actions taken by brothers on both sides during the war displayed the highest virtues of what our institution teaches, humanity and sense of duty to our fellow Masons and brothers. They demonstrated that even while tested, the bonds of fraternity and friendship still endure during the hardships and turmoil of war. The Civil War demonstrated that not only Masons in Rhode Island, but the whole United States of America would ever remain a brotherhood undivided.

W∴ Paul Fetter III, P.M.